Very nearly every organism on Earth has hard-wired within it an unconscious will to survive at all costs. I say “unconscious” because this drive exists in species that don’t even have consciousness; everything from banana trees to bacteria are pre-programmed (without knowing it) to survive above all else. The ones that weren’t programmed that way by their genes simply don’t pass on any more of those genes. Natural selection is brutally simple.

The survival instinct is still within humans too, of course. And once in a while—rarely for most of us—it gets put to the test directly. Here are the true stories of the three greatest survivors in human history, by my reckoning. There may have been more “adventurous”, “long-shot” survival stories out there—Shackleton’s expedition or the crew of Apollo 13—but those men had companionship, camaraderie, and others back home willing to mount rescue efforts. The following three survivors had no guarantee of that stuff, therefore having to grapple with perhaps a more lethal hazard to the human brain: Total, uncaring isolation.

Their stories are illustrative of the strength of the human survival instinct that is physically within each of us, right now.

Ada Blackjack, 1898 – 1983

It’s difficult to grasp how isolated Wrangel Island is. It’s over a hundred miles north of the Siberian mainland—so, two hundred miles from the nearest tree—and at least 600 miles north of the nearest good-sized city (Nome, Alaska). And these aren’t easy-sailing miles, mind you. For most of the year, and sometimes for the entire year, the Chuchki Sea around Wrangel Island is entirely frozen over, encasing it in a limitless expanse of crushing, colliding, snowy sea-ice. Sailing over it is out of the question. Even walking over it ranges in difficulty from “extremely dangerous” to “impossible”.

The blue sea is misleading. Most of the year it’s actually ice.

The blue sea is misleading. Most of the year it’s actually ice.

So it was, of course, uninhabited when modern humans finally reached it in the 1880s. And, as modern humans are wont to do (even with a remote and uninhabitable island filled with polar bears), we began squabbling over who owned it. The Russians first asserted control, and a Canadian named Vilhjalmur Stefansson decided that would never do. He planned to send a group of settlers over the frozen ocean to live there for a while, so Canada could claim it as their own later on. He conscripted four young men, all in their twenties, for the journey, and planned to send along a few Inuit families with them for support. But with the expedition scheduled to set sail from Nome, the promised Inuit families didn’t show up at the dock. Well, one Inuit woman did. She was named Ada Blackjack.

When she tried to back out, the group promised they would find more willing Inuit families on the way north, so she agreed to stay on. They did not find any willing Inuit families on their way north. The settlers, four men and Ada, landed on Wrangel Island in September of 1921.

Looks like a fun place.

Looks like a fun place.

Their supplies lasted all winter, and in the short spring/summer of 1922 they began hunting to feed themselves until the next supply ship could arrive in August. But the summer was a short, frozen one, and Wrangel Island remained inaccessible due to sea-ice all that year. They couldn’t find enough food to feed themselves. And the supply ship never even got close.

Conditions worsened, and the frozen settlers began to starve. In the middle of second winter, 1922/23, their rations ran out, and the only edible thing for hundreds of miles (besides each other, the dogs, and the expedition’s cat) were polar bears. It was around this time that three of the men decided to try walking south to Siberia. They didn’t include Ada, because the fourth man was too ill to come along, and they wanted Ada to stay and take care of him on the island. Or, more likely, they secretly thought the sick man and Ada would slow them down and die along the way anyway, so they might as well just stay back and die without burdening anyone.

So the three men left. They never made it to civilization, likely dying of starvation, scurvy, or just taking a wrong step and slipping through the sea-ice at some point in their walk across an endless frozen ocean.

Ready to walk over one hundred miles across sea-ice?

Ready to walk over one hundred miles across sea-ice?

Ada and the sick guy, Lorne Knight, spent the rest of the winter in total darkness (the winter sun doesn’t rise this far north, of course). Knight was bedridden, likely suffering from scurvy, and delirious. In June, Knight died. Ada Blackjack was now utterly, utterly, incomprehensibly alone. She was 24 years old.

She realized if help ever did come—and, to be frank, it probably wouldn’t—it could only reach the island late in summer. She didn’t have enough food or fuel to survive that long. So, one of the greatest survivors in human history did the only thing that could possibly save her: learn to hunt among the polar bears, alone, in the subfreezing polar tundra.

Not to put too fine a point on it, but this idea was almost laughably futile. The four strong men (now all dead) had attempted to self-provide food the previous year. They were excellent hunters, with plenty of experience and ammunition, and had hunting dogs. And they still failed miserably. Ada had none of their advantages.

Ada perhaps had only one thing that they didn’t: A child back home. She had taken this job in part to earn enough money to care for her son (he had tuberculosis). Her husband had drowned a few years prior. And now, 600 miles across the sea and ice, she had no choice but to stay alive so her only son wasn’t orphaned.

Survival was impossible. But survive she did, mostly by trapping foxes, collecting bird egg and hunting seals (burning their blubber for light and heat). Her months of total, crushing despair on Wrangel Island must’ve been beyond words. She never spoke of it much after she returned home on a supply ship that found her in August of 1923. She only spoke about it when she had to: she was accused of “not doing enough” to save the useless sick man she was abandoned with (Knight’s family eventually “vindicated” her, for whatever that could possibly be worth).

After getting home, she married twice more, had another son, and lived to old age in relative peace. Her gravestone reads “Ada Blackjack: Heroine of Wrangel Island”. She might not have saved anyone except herself, but even so, this inscription doesn’t nearly do justice to one of the greatest survivors in history.

José Salvador Alvarenga, b. 1977

José Salvador Alvarenga was born and raised in El Salvador, and by 2012 had made himself a checkered past. He fathered a daughter and then fled north—his cousin says after being stabbed in a barroom brawl—to make a new life in the United States. However, he never made it further than Mexico. Settling in his early thirties near an oceanside town in Chiapas, he was nicknamed “Piggy” (“Chancha”, in Spanish) by the locals, due to his appetite and portly build. He soon took up fishing, and quickly became adept at deep-sea hauling during the day and drinking heavily at night.

On November 17th, 2012, Salvador set out on a two-day fishing trip with a younger companion he hadn’t met before, Ezekiel Córdoba, nicknamed “Piñata” (nicknames are big in Latin America). Piggy and Piñata, after taking a large haul that day, got caught in a massive storm. Two other boats were sunk in that storm, but theirs survived (their outboard motor did not), partially because Salvador decided to toss their entire catch overboard, stabilizing the 24-foot boat. After three days, with the storm still raging, the local police called off the search for all lost vessels. Salvador and Ezekiel, floating helplessly west, were presumed dead.

24-foot boats, similar in construction to Salvador’s.

24-foot boats, similar in construction to Salvador’s.

Things get bleak quickly as a castaway. The thirst comes first, and will generally kill you within a few days. To head this off, Salvador and Ezekiel caught fish, turtles, and inquisitive seagulls with their bare hands, and drank their hot blood. This kept them hydrated. Then there’s the sun. Within a few weeks, the merciless sun will usually cause burns and sores all over your skin, which get infected, and kill you shortly thereafter. To combat this, Salvador and Ezekiel spent all day huddled in an overturned ice chest, just big enough to shelter the both of them from the sun. And then, there’s the merciless onset of depression and mental deterioration. Ezekiel began succumbing to this after about four full moons (they had lost track of the days, and had no other way to measure time).

After four months at sea Ezekiel began refusing food and rainwater. He was delirious and despondent. Salvador was helpless, watching him convulse, and then die in front of him.

Salvador cracked. He didn’t seem to realize what happened. He conversed with the corpse for a few days as if it were still alive, until it was stinking and no longer able to function as a suitable fantasy companion. He pushed it overboard and wondered how long he should wait before killing himself.

Solitude at sea—the emptiness stretching distances beyond the mind’s ability to fathom in all directions—is a special type of psychological torture. Coupled with a diet of raw jellyfish and turtle blood (and the accompanying intestinal parasites), it’s difficult to imagine a sane person surviving for more than a few weeks alone. The fact that Salvador had survived with Ezekiel for as long as they did was already quite remarkable. But Salvador, for no other reason than the sheer human drive to live, kept sticking his hands in the ocean and plucking out jellyfish. He kept ducking into his ice chest all day, and pacing the boat at dusk. Day after day, moon phase after moon phase.

His brain, mercifully, gave him vivid hallucinations throughout the day. This must have been a primal genetic survival mechanism; without them, he says, he surely would have succumbed.

Salvador continued to drift west. He had now been at sea by himself as long as he had been at sea with Ezekiel. Around this time he would have been breaking all known records for length of time spent adrift at sea, although he likely did not realize it, or care. All he knew was catching turtles and interacting with his hallucinations. He later recalled the only reason he didn’t kill himself was that he believed those who commit suicide do not reach heaven in an afterlife. I believe this is just a natural extension of our will to survive (even after death).

It had now been about 14 full moons since he had set off that day in Mexico. Piñata had died a lifetime ago. Salvador had been adrift at sea for longer than any other person in recorded history. And then one morning he noticed a large number of seagulls over his boat. He’d seen birds, of course, but a flock so large wasn’t just odd; it meant land had to be near. Hallucination or not, he got excited.

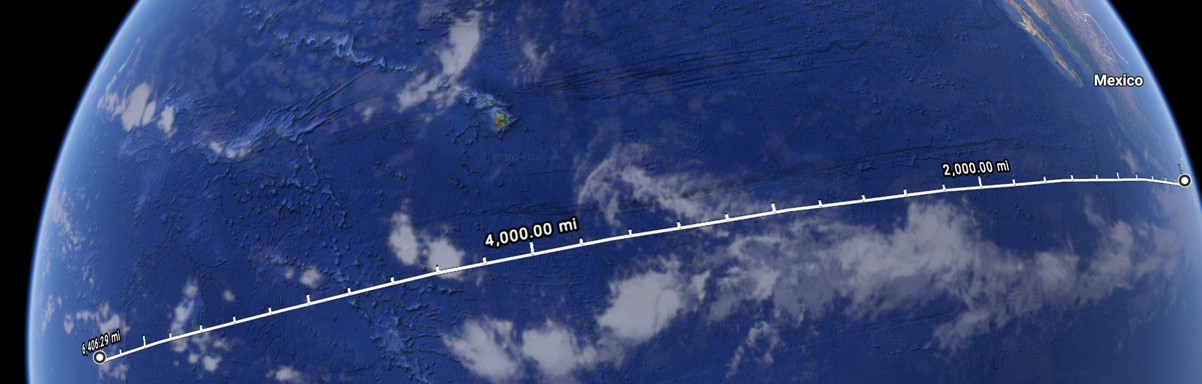

A rough approximation of Salvador’s drift.

A rough approximation of Salvador’s drift.

He spotted a tiny island—the Tile Islet of the Marshall Islands, as it turns out—and saw land for the first time in 438 days. Struggling, splashing and crawling up the beach, he collapsed and slept for hours. He finally awoke and staggered towards the trees, hoping the island was inhabited. It was, in fact, and he found two of its only residents: Amy Libokmeto and Russell Laikedrik. Salvador was naked and holding his knife, hadn’t cut his hair or walked on land for over a year, and only shrieked at them in Spanish, but the islander couple took him in anyway. They cooked him pancakes and alerted the local police officer. If he hadn’t landed on this tiny atoll in the middle of the Pacific, he likely would have kept drifting west for another year, at least.

Salvador, after his ordeal

Salvador, after his ordeal

He was taken to the hospital and his health stabilized. After a few weeks he was well enough to travel home, back across the Pacific. The journey that took him more than a year to make in a boat took him only half a day to retrace in a jet.

Salvador is still alive today, but as you might expect, not without his psychological and social problems. He was rehabilitated and returned to his estranged family in El Salvador, where he was greeted with lawsuits from Ezekiel’s family, and then from a lawyer he’d hired.

Such is life back home when you’re the greatest living survivor on Earth.

Marie Dorion, c.1786 - 1850

You may have heard of Sacagawea. She was the young Native woman enlisted (with her husband) by the Lewis & Clark expedition as an interpreter on the first ever trek across the American continent. Saving the group from starvation and war, she’s somewhat of a folk heroine today, with hundreds of statues and parks & trails named in her honor. She even has her own US coin.

You may not have heard, however, of the second woman to cross the continent. Her Native name seems to have been lost, but she went by Marie Aoie when she married the French fur-trapper Pierre Dorion, and took his last name. Pierre, half-indigenous himself, signed on to join billionaire John Jacob Astor’s “Overland Party”, leaving St Louis to loosely retrace the Lewis & Clark route from just a few years earlier. The purpose of this trip wasn’t exploration; it was to establish Astor’s fur-and-goods trading empire in the remote Pacific Northwest territory.

Astor’s plan—named the Pacific Fur Company—was enormous in scope. He’d send a large party overland, across the merciless Rocky Mountains, mostly through lands entirely unseen by European settlers (this was well before the Oregon Trail… In fact, this expedition would end up discovering most of the Oregon Trail). A majority of the indigenous tribes they would encounter had never before seen a white man. At the same time, Astor sent a ship around the tip of South America and back up the west coast, to rendezvous with the Overland Party at the mouth of the Columbia river and establish the first American trading outpost on the West Coast. It would be named Astoria. Astor wasn’t particularly humble in this regard.

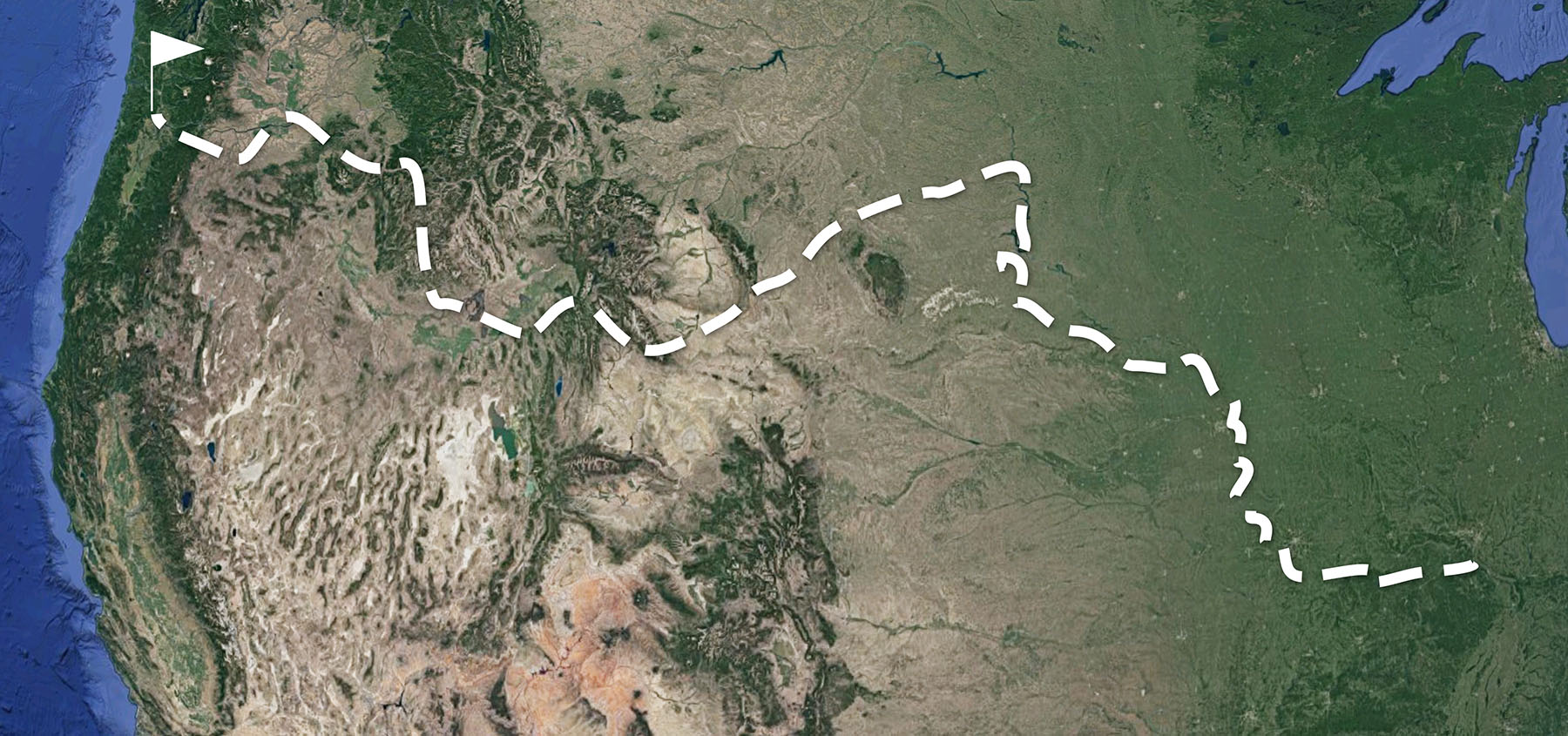

The proposed route. What could go wrong?

The proposed route. What could go wrong?

Marie Aoie embarked from St Louis in 1811, destined for the Pacific. Adding to the extreme difficulty, she brought along her two infant sons. Also, she was pregnant. And they were preparing to basically walk, paddle and ride something like 3,700 miles across uncharted wilderness. Marie wasn’t yet 25 years old.

The horrors the Overland Party endured over the next 12 months rival anything in American 19th century exploration. Lost for weeks without food or water in the hostile Hell’s Canyon region of the Snake River, many succumbed to the elements, starved, or “went mad”. After slaughtering their horses for meat, Marie had to trudge through the snow, carrying her two young boys on her back. Eventually most members of the expedition resorted to eating their beaver pelts and moccasins. The party fractured into smaller groups, and one such group—who said one of their men “wandered off”—could never shake the suspicions of cannibalism. Marie eventually gave birth at a Native settlement near the present-day Oregon/Idaho border. The newborn died within a week. Marie continued on.

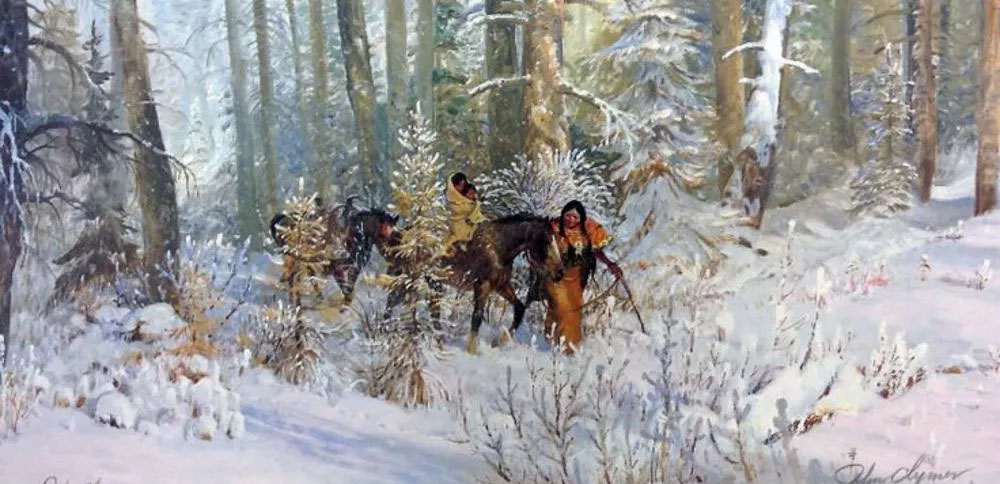

“Hope your babies don’t mind a few bumps, Madame Dorion!”

“Hope your babies don’t mind a few bumps, Madame Dorion!”

After reaching the Pacific, and with Astor’s trade post on the verge of collapse (the War of 1812 had broken out and the British would conquer and rename the fort shortly thereafter), Marie, her husband and two surviving children traveled to another trading post further inland, where they would live as fur trappers with several other men. In early January, 1814, one of the men stumbled back, bloodied and beaten, to the cabin where Marie was cooking with her two sons. He told her the entire party had been ambushed by a hostile Native tribe, apparently as revenge for a wrongful murder one of the Overland Party leaders had ordered a few months earlier. Everyone else, including her husband, was dead. Marie put the injured man, named Le Clerc, on a horse, mounted another with her children, and rode to the nearest cabin, a five day trek. One frigid night on the journey, hiding from the vengeful band of Natives, Le Clerc died.

The Snake River, in winter

The Snake River, in winter

Marie buried him, packed up her children, and continued on. When she finally reached the cabin—the only outpost of white civilization in the territory—she found it empty and covered with blood. Every person who she knew in the region had been murdered. She was now facing winter, with two young mouths to feed, in one of the most brutal wildernesses of North America. There was no one alive who could help her.

And she couldn’t stay at the cabin. If she were found by the hostile band of warriors, she’d be murdered as well.

Editor’s note: As a brief interlude, I want to mention sometimes I get cold if I leave the air conditioner on too long and it dips to 67 degrees Fahrenheit in my apartment.

Anyway, Marie did what any 28 year old widow with two children to keep alive in a remote, sub-freezing mountain range would do. She traveled high through the mountain snow, found a ravine, slaughtered the horses, smoked their meat, made clothes and shelter of their skin, and braided intricate rodent traps with their mane hair. She did this methodically, to perfection. She caught and smoked enough meat, and kept her children dry enough, to survive a brutally cold winter of unending misery.

Artist's impression of what Marie may have looked like

Artist's impression of what Marie may have looked like

In late March, at first snowmelt, she took her children west on foot, scaling down the mountain range, until she happened upon a friendly tribe of the Walla Walla people. They fed her to regain her strength, then accompanied Marie to the nearest fort. When she returned, Astor’s men wrote more passionately about their grief at the loss of the trading post than what Marie had just endured.

Marie remarried twice, and had three more children, before dying a respected member of the small community of St Louis, Oregon.

It’s worth noting that Astor’s empire failed, at the cost of 61 lives of the 140 men he sent to establish it. And some of the survivors, suffering from what we’d now recognize as PTSD, were psychologically damaged beyond repair, a few attempting suicide. Astor, from his warm mansion in Manhattan, summed up his failure: “My plan was right, but my men were weak. Time will vindicate my reasoning.”

He neglected to even mention Marie Dorion.