If you aren’t familiar with Markov chains, well, don’t beat yourself up over it. Their simplest summary is way too simple (“a state that can be immediately deduced from an earlier state”, thanks Wikipedia!) and yet their real-world applications are ferociously complicated. There’s not much in-between. They’ve been around for a while but have found mainstream recognition only recently, as computing power is finally becoming cheap enough to calculate some huge, truly interesting states from “stateless” data.

One fairly mind-blowing use of Markov state computation is the Deep Pink chess engine: It was trained purely by “observing” billions of chess moves. By using these to predict a strong “next state” of a chess game, it became a very good chess player without ever being programmed to understand how any single piece moves. It technically doesn’t know what chess is, it’s just really good at predicting what the next state of a chess board should look like.

Another neat use of Markov chains is in natural language generation. You can feed a Markov-inspired language generator a bunch of text (the more the better) and it’ll “predict” any amount of words, sentences, and paragraphs that might be “coming up next.” Now, it really doesn’t predict anything, because text generators can currently only analyze syntax, grammar, and vocabulary; meaning is entirely lost to the computer, so it comes up with text that kinda sounds like human language, but is basically gibberish. Which leads me to Finnegans Wake…

If you aren’t familiar with Finnegans Wake, don’t beat yourself up over it. It was written by world-famous novelist James Joyce between 1922 and 1939, and English majors are still losing nights of sleep trying to figure out whether it actually means anything. And I don’t mean that in a sort of subjectivist, “Does anything really mean anything?” kind of way, brought up in passing by elbow-patched University professors over steeping teabags in dusty lounges on the edge of campus; I mean there still is literally no consensus—academic or otherwise—on whether it is 600 pages of entirely made-up nonsense.

A typical passage from Finnegans Wake

A typical passage from Finnegans Wake

Joyce may have been playing a joke on the literary community, or, he might have changed the very definition of the novel. We don’t know. And barring any new personal revelation, we might never. I was leaning, personally, toward believing Joyce: Reading a few passages from Wake always overwhelms me, but there is an undeniable, unmistakable thread of constancy running through it, I find. It might be as little as two separate words a paragraph apart, but something always seemed to tell me that each page meant something deeper, and I was willing to give the author the benefit of the doubt.

Until I ran it through a Markov text generator.

When I found this simple Markov text generator a few days ago, I almost immediately knew I had to train it on Finnegans Wake. While analyzing Wake, humans get stuck on things like trying to decipher the meaning behind one of Joyce’s forty-five letter words with eighteen Zs in it. But a Markov text generator would just note it and move right along, using it only to inform its memory store that long words with lots of Zs are slightly more likely to occur. I coded the Markov program to read Wake, parse the results, and then begin predicting more of its text, based on its entire grammar, syntax, and vocabulary at once. This type of analysis, once nearly impossible, now takes only minutes.

And when I saw the results, I almost didn’t believe it. Feel free to try telling the difference yourself.

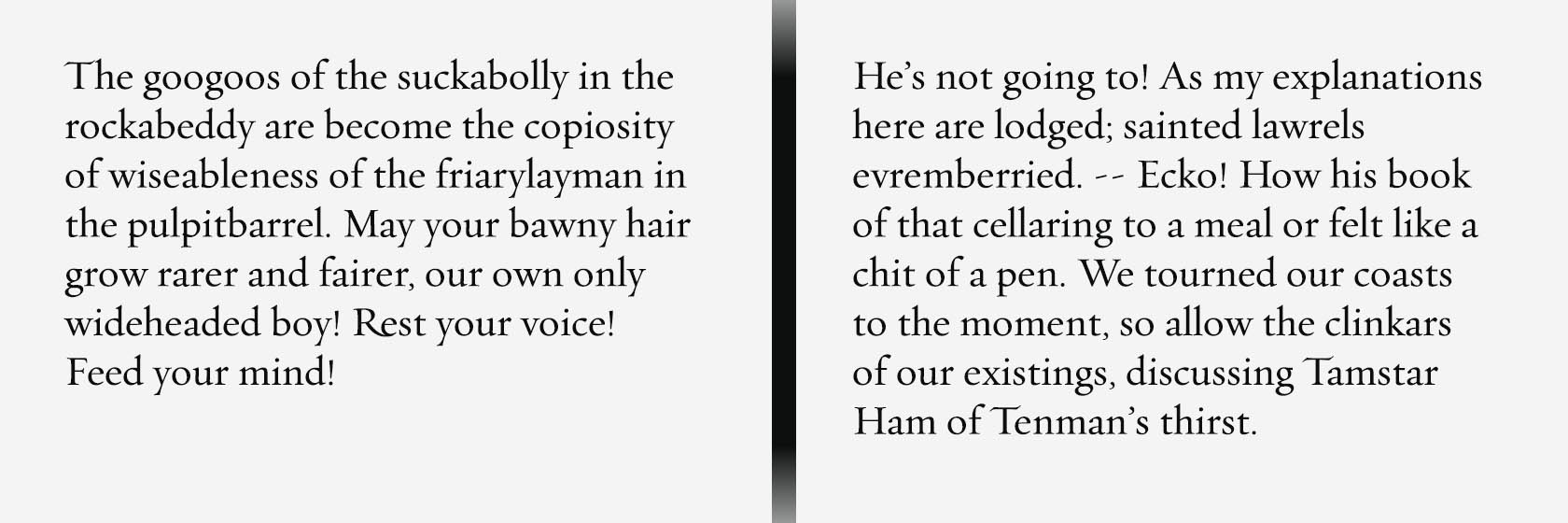

A passage from Wake on the left, and a Markov generator on the right.

A passage from Wake on the left, and a Markov generator on the right.

In many cases, the language generator actually makes more sense than the original text. The output, entirely devoid-of-meaning, seems to equal the original text in substance as well as style. I watched the results coming in—unable to tell the difference between the original and my output more than 80% of the time—in a state of disbelief. You could easily insert the computer’s output anywhere within Wake’s 600 pages and practically no one, no one in the world, would be able to tell.

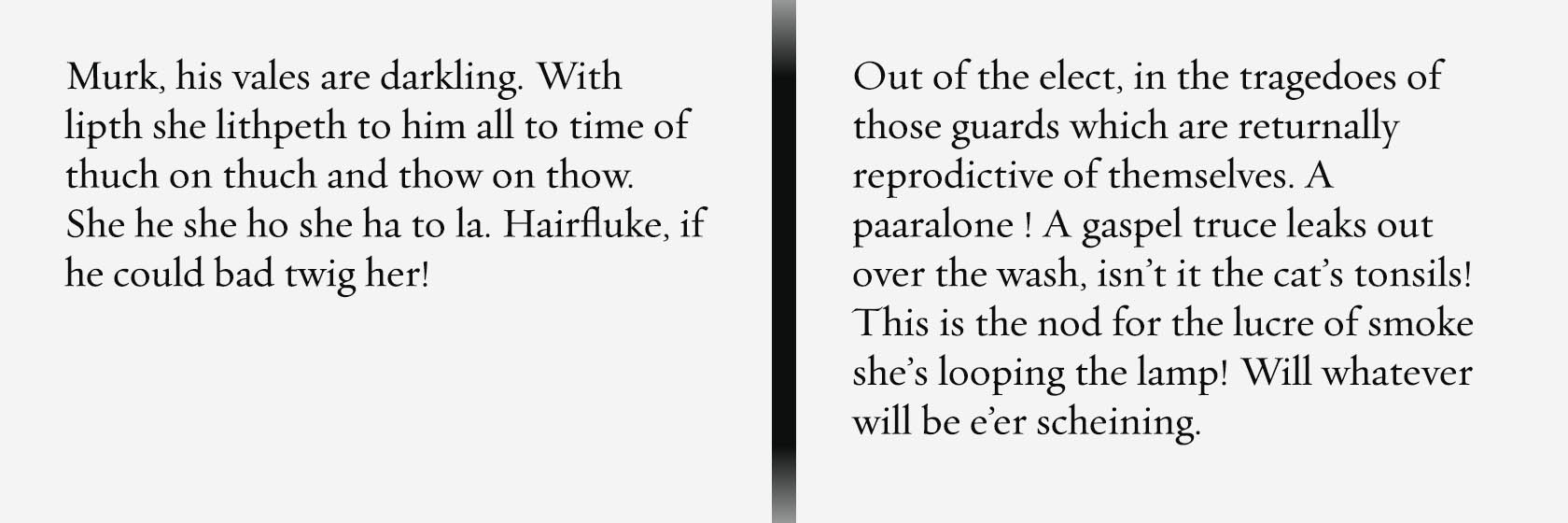

Can you tell which passage is from Wake, and which is computer-generated?

Can you tell which passage is from Wake, and which is computer-generated?

So does that settle it? Was Joyce a fraud? Is his text, now indistinguishable from gibberish (for me, anyway), as devoid of narrative as my program’s code? Not so fast.

I’m no English major, but I can recognize a few things we can’t take away from Wake. Firstly, the magnificently inventive vocabulary was entirely Joyce’s own. Sure, my program might be able to reproduce it, but it would never have been able to invent it. Even if the novel itself were meaningless, if you find meaning within a word, that honor belongs entirely to Joyce.

Secondly, even if the artist’s intent could somehow be proven machine-replicable, that doesn’t make it less valid. We could build a machine to paint like Van Gogh (or certainly Pollock), but this wouldn’t diminish the impact any individual work of art had on its observers. Perhaps part of the artist’s intent is to convey chaos, or even machine-replicability! For all I know, if Joyce were to rise from the grave and see the output from my Markov app, he might have a good laugh, lightly edit for theme, and happily publish it as Finnegans Wake Part 2: Even Wakier. And would that surprise anyone??

I have honestly lost my note on which passage is which; I really don’t know which is Joyce and which is Markov-generated.

I have honestly lost my note on which passage is which; I really don’t know which is Joyce and which is Markov-generated.

And thirdly, just because I can’t tell the difference between the two about 80% of the time, that doesn’t mean no one can. There might be literary students who can tell the difference a vast majority of the time. And, even though that shouldn’t affect my personal opinion on the work, it certainly means more learned academics might reach a vastly different conclusion that I do, even with the same data.

In the end, I have to admit my opinion on Wake has changed because of this. I’m willing to accept now, fully, that its internal cohesiveness is no more difficult to generate than nonsense. But, my admiration for it, and certainly for Joyce, has actually appreciated.

If nothing else, he was a Markov language generator 80 years before they were invented.