Developing and maintaining a successful web app sometimes requires decisions that are really big and highly complex. Like routing, linting, testing, CI/CD strategies, etc… Those things could each be their own six-part blog post, and you’d still barely scratch the surface. Other times these decisions are tiny, clever tricks you can start using right away, costing you almost nothing. I like those kinds of things better. And when I find one, I like to write a few paragraphs about it to remember to keep using it, and hey, I might as well share a few of them with you now.

So here are the top three small things I think you should be using today to make your web application more stable, more inclusive and all around way better.

1. Make all of your API calls fail randomly in dev

I love this one. So brutal in its simplicity, but has such an enormous positive effect on your end UX. I’ve used it for years now after a coworker showed it to me and I’ll never go without it again. The trick is this: Every time you hook up a fetch from the browser, or a GET from a server, or anything that talks to any external data source at all, make it fail like 10% of the time while you’re running it in development mode. It doesn’t have to be fancy, it can be as simple as this:

const oneInTenChance = Math.floor(Math.random() * 11) === 10;

if (oneInTenChance) throw Error('Please try again later');

Now stick that in your client-side component (or action, or what have you):

try {

const oneInTenChance = Math.floor(Math.random() * 11) === 10;

if (oneInTenChance) throw Error('Please try again later');

const resp = await fetch(`/foo/bar`, { // [...etc]

}

} catch (e) {

console.log("Error:", e);

}

… or better yet, stick it directly into your API server’s routes:

app.get('/api/some/route', (req, res) => {

const oneInTenChance = Math.floor(Math.random() * 11) === 10;

if (oneInTenChance) throw Error('Please try again later');

res.send(

`foo = { "bar" }`

);

});

(Just don’t forget to remove this when you run in production mode, lol)

This has the wonderful effect of making you mad as you develop the client software, and you yourself become the user, frustrated with a random API error here or there. You simply can’t ignore it. Gracefully handling errors has got to be one of the top five things that separate a great app from a fly-by-night operation, and your users absolutely can tell the difference. Start pissing yourself off today so you don’t piss off your users tomorrow.

2. Use non-traditional mock data

And by “non-traditional” data I mean “not White-Euro-American, culturally Western” data. Using John Doe/123 Fake Street as all of your mock data sucks. Sorry folks. This isn’t some leftist communist globalist manifesto thing, this is just practical web development. You should make a habit of using entirely different mock data sets than ones you’re most comfortable with, starting today. I’ll show you why.

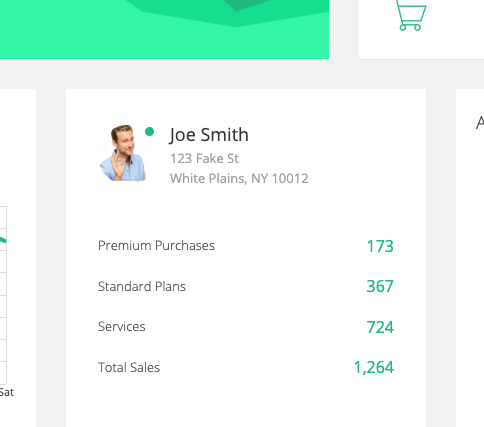

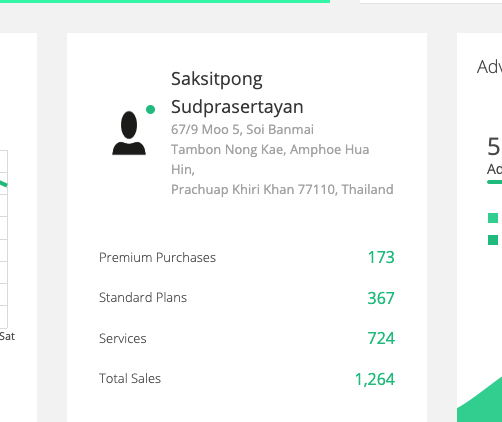

The design…

The design…

…vs reality

…vs reality

App designs and implementations using “John Smith”-style mock data will be unnecessarily brittle and usually too constrictive, not allowing enough space for longer text nodes or different data shapes. The fixes are almost always trivial—ensuring an element flexes or a text node truncates at a certain length, etc—but if your designers and developers and product owners all use the same kinds of names and addresses, you may never know you needed to implement these tiny fixes until it’s too late.

This also extends to non-visual development as well. All too often you’ll see a unit test that looks like this:

// Test our buildEncodedURLParams() function

const mockData = {

name: "John Doe",

email: "john@example.com",

phone: "123-456-7890"

}

const urlPath = buildEncodedURLParams(mockData);

expect(

urlPath.length.toEqual(

mockData.name.length +

mockData.email.length +

mockData.phone.length +

3 // encode the "@" symbol!

)

);

That test is way too brittle. Without even knowing what buildEncodedURLParams() does under the hood, you simply can’t expect the test as written above to capture any edge cases, and essentially anything that deals with non-culturally-Western data! To better generalize a unit test, which in many ways is exactly the purpose of a unit test, we should try thinking in data units that are outside our own common professional experiences, precisely because the ones within our common experiences will be tested naturally during development! In other words, a far better mock data set would be this:

// Test our buildEncodedURLParams() function

const mockData = {

name: "张伟",

email: "zhāngwei@xn--s7y.co",

phone: "021-15545638, ext. 034"

}

// [...]

That test right there makes for a more solid, scalable web app. And it’s free to implement. To start generating better data right now just use something like ChatGPT or you can Google for a name generator that lets you select different cultures/locales/nationalities when making fake personal data. Make this a habit and soon you’ll cringe every time you see old John Doe making your tests and UIs brittle.

3. Tokenize all of your copy

This one took me a while to fully commit to, but now that it’s a habit, I never want to go back. Here’s the gist. All of the words on your web app need to be tokenized. So, not this:

but rather, this:

// tokens.js file

const tokens = {

sendEmail: "Send email"

};

// component file

import {tokens} from 'tokens';

“Oh my god that’s way too much work, our website has like a million words!”, “Never happening, I can’t be bothered to do this.”, “Good luck getting all our developers on board! They’ll never do this”, yeah yeah, I get it. I was there too. I said each one of those things. But guess what? It’s not actually that bad. It’s only a few seconds of extra work per token, and when new developers contribute to the codebase, they all learn very quickly to tokenize their copy.

For some context the Elastic Support Portal—a big web app I led the development on—is fully tokenized and the grand total number of tokens is currently… 366. Not that bad.

And what does that enable us to do? Internationalization. Or, i18n for short. When we want to roll out a new version of the app in, say, Greek, all we have to do is add translations of the tokens that are already there:

const tokens = {

english: {

sendEmail: "Send email"

},

greek: {

sendEmail: "Στειλε το"

},

}

By plugging those tokens into any i18n library, what you get is almost frighteningly powerful. Now, paying an interpreter to translate a few hundred JSON values then do a quick scan of the app for completeness is almost a negligible cost compared to the end result: A native app experience in any language or location. And that’s not even getting into how easy it will be to audit all the language on your website if the need arises; delivering a copy of all the text used in your company’s app to the legal department will now take roughly 10 seconds.

“Well, what about currencies? Or date formats? Or pluralization??”. Valid concerns! And each of those are addressed by one of a number of i18n libraries out there.. but they all start with tokens. The work you do now will not be wasted; it’ll all port over easily to whichever fully-baked i18n solution you choose.

There are a million ways to go from here, like the popular i18next, but it all starts with one thing: { tokens.startTokenizingNowExclamationPoint }